| As the 2020 NFL season approaches its halfway mark, millions of fans are following the action on the field to see if their team will make the playoffs. However, behind the scenes, negotiations are taking place between the NFL and various media conglomerates that will shape how fans consume professional football for the next decade and beyond. Immediately following Super Bowl LVI on February 6, 2022, the current NFL broadcast contracts are set to expire. These contracts dictate which networks broadcast each game, what time slot each game is scheduled for and on what devices viewers are able to watch the games. The current contracts were negotiated in 2011 and are worth over $5 billion in total each year. During previous seasons, the NFL’s broadcast partners publicly stated that it would not start negotiating contract extensions until the NFL reached a new collective bargaining agreement with the NFLPA. The NFL players association approved this CBA on March 15, 2020, leading many to speculate that television negotiations would begin shortly after. However, earlier that week, Utah Jazz center Rudy Golbert tested positive for COVID-19, sending all of professional sports and American society into uncharted waters. Both the NFL and its broadcast partners preferred to delay the television contract negotiations. The NFL executives were busy adjusting the upcoming season for an unimaginable virus, while television networks wanted to wait and see what effects the pandemic would take on professional sports and viewership patterns. Now that the season is underway as “normal” and television ratings have largely stabilized, preliminary contract negotiations are taking place. Below, I examine the history of NFL television contracts and the economic considerations behind them, before speculating what the next round of television contracts might look like. |

NFL Television History:

| When the AFL and the NFL merged in 1970, Commissioner Pete Rozelle was committed to broadcasting every game in the new league on television. Rozelle as Commissioner of the pre-merger NFL oversaw massive growth in popularity of professional football, primarily because of its exposure on television. The new league split its broadcast rights between CBS and NBC. CBS would broadcast every game where the visiting team was from the NFC, while NBC would broadcast every game where the visiting team was from the AFC. Rozelle appeased ABC, the third major network at the time, by giving the network rights to a single game every week, an opportunity which famed executive Roone Arlidge turned into Monday Night Football, one of the longest running and most successful prime-time programs in American television history. Rights to the Super Bowl rotated between CBS and NBC, depending on which conference was hosting that year. This arrangement satisfied the NFL and all broadcasters. The league ensured that every game would be broadcast on television, while each network could build its programming schedule around the popular NFL. This allocation remained consistent until 1986. Upstart cable network ESPN had prepared to broadcast USFL games on Sunday evenings for the league’s planned 1986 season. However, when the USFL disbanded prior to the season, the NFL secured ESPN as a broadcast partner for the following season. ESPN was given a single game a week on Sunday evenings for the second half of the season, which was branded as “Sunday Night Football”. Sunday Night Football was a success, prompting the NFL to expand it to the entire season three seasons later. Cable superstation TNT purchased the rights to Sunday Night Football for the first half of the season, while ESPN retained the rights for the second half of the season. Commissioner Paul Tagliabue credits the addition of Sunday Night Football as transforming the NFL from “a potential six- or seven-hour television experience into a twelve-hour television experience." The first major broadcast realignment occurred in 1993 when the fledgling Fox Network made a bid for NFL broadcast rights. Fox was only several years old at the time and was far behind the “big three” broadcast networks in viewership and reputation. The addition of NFL coverage would establish Fox as a major network in the United States. Fox’s interest in NFL rights created a game of musical chairs, where one network was bound to be left without a seat. Fox secured the NFC package with a $395 million bid, far greater than the $290 million offered by CBS to retain the package. CBS felt immediate backlash, with several affiliate stations in NFC media markets (including Detroit, Atlanta and Milwalkee) dropping CBS in favor of Fox. CBS struck back at the next round of negotiations in 1998 by outbidding NBC for the AFC broadcast package, offering $500 million per season. NBC attempted to purchase the rights to Monday Night Football, but ABC successfully retained the broadcast package. In the following years, NBC tried to fill the void in its programming schedule left by the NFL by televising Arena League games and co-launching the first iteration of the XFL in conjunction with the WWE. However, neither venture proved to be a successful substitute to the NFL. Additionally, during the 1998 renegotiations, ESPN secured the rights to the entire season of Sunday Night Football, ending TNT’s coverage of the NFL and leaving ESPN as the only cable broadcaster of NFL games. During the 2006 negotiations, NBC reclaimed broadcast rights for the NFL by purchasing the rights to Sunday Night Football. ESPN, the previous broadcaster of Sunday Night Football, purchased the Monday Night Football package from its sister network, ABC (Both have been owned by the Walt Disney Company since 1996). Fox and CBS renewed their agreements for the NFC and AFC packages, respectively. The most recent broadcast contract renegotiations occurred in 2011 and went into effect for the 2014 season. All networks retained their previous packages, although the cost of each contract was increased significantly. NBC pays $950 million per year for Sunday Night Football which includes one game a week on Sunday evenings in addition to a game on Thanksgiving, the NFL Kickoff game on the Thursday after Labor Day, and two playoff games. ESPN pays $1.9 billion per year for Monday Night Football, which includes 17 regular season games (Two on Week 1 and none on Week 17), a single playoff game and the pro bowl. CBS pays $1.03 billion per year for the AFC package, which includes all Sunday afternoon games where the away team is from the AFC. Similarly, Fox pays $1.1 billion per year for the NFC package, which includes all Sunday afternoon games where the away team is from the NFC. Both the AFC and the NFC packages also include rights to four playoff games. Under these contracts, the rights to the Super Bowl, the most-viewed television program annually, is rotated between NBC, CBS and Fox, the three broadcast networks with NFL television rights. Additionally in 2014, the NFL made a fifth package available for networks. Thursday Night Football has been played since 2006, when it debuted on NFL Network, a cable channel owned entirely by the league. The decision to broadcast Thursday Night Football exclusively on the network was used as leverage for cable providers to carry the channel. However, the NFL decided to sell the rights to these games starting in 2014. Unlike other packages, Thursday Night Football was initially sold on a year-by-year basis. CBS paid $275 million for the package in 2014, which increased to $300 million for the following season. For the 2016 and 2017 seasons, Thursday Night Football rights were split between NBC and CBS for a cumulative $450 million per season. Starting in 2018, the NFL sold Thursday Night Football to Fox in a four-year deal, worth $660 million per year. With this agreement, all five packages are set to expire following Super Bowl LVI on February 6, 2022. |

Economics of TV contracts:

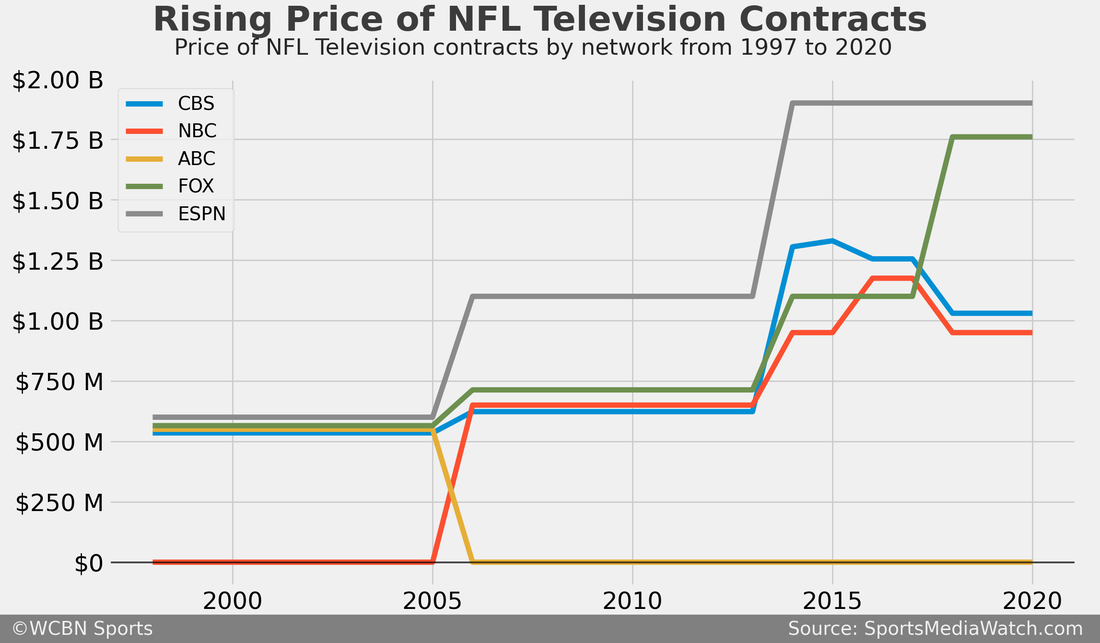

| Before investigating what the next round of NFL contracts might look like, it is worth understanding the economics behind the NFL’s television contracts. Below is a graph of how much money each network has paid for NFL broadcast rights since the 1997 contract negotiations: |

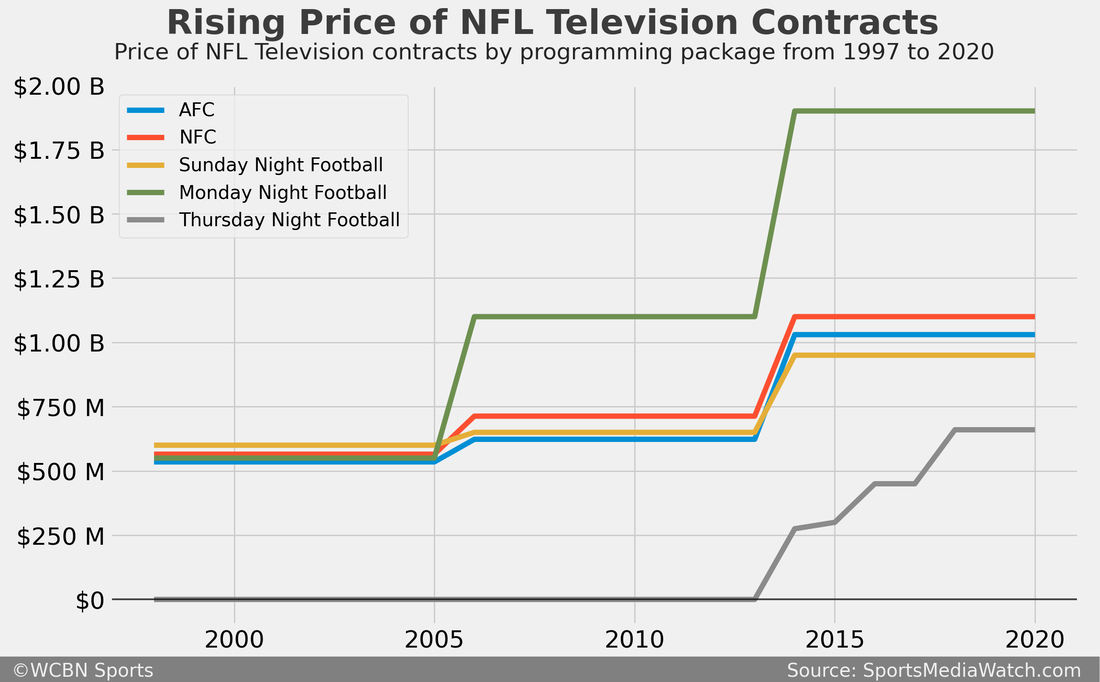

| As expected, the value of NFL contracts have generally increased in value over the past two decades. This becomes more clear when the contracts are grouped by programming package, rather than network: |

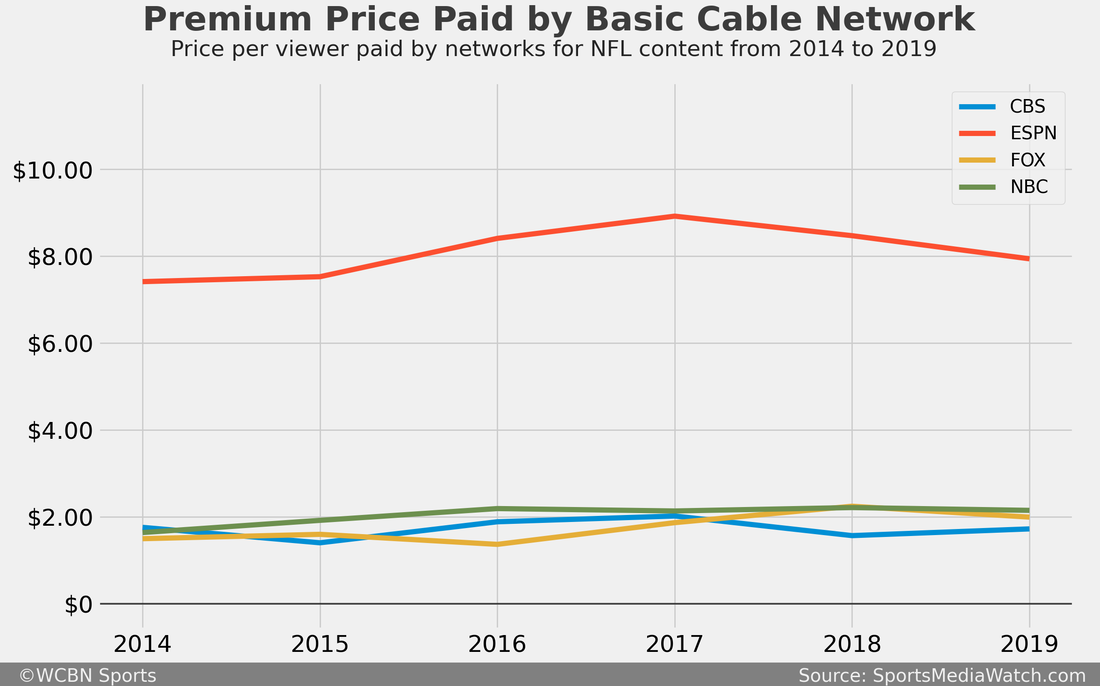

| But why do certain networks pay more than others? Looking at only the contract value, it appears that NBC and CBS have a better deal than Fox and ESPN. However, this assumption isn’t necessarily accurate because each programming package comes with a different number of games and takes place during different time slots. For example, although NBC only broadcasts one game each week, the primetime slot on Sunday evening draws more viewers than AFC and NFC coverage on Sunday afternoons. If some packages draw more viewers than others, paying more might be worth it. To analyze each contract accurately, you need to account for the total NFL viewership that each network receives over the course of a season. Total viewers over the entire season range from 200 million to 700 million, depending on the network (This is not the number of unique viewers, since many fans watch more than one game each season). Dividing the cost of each NFL contract by the total viewership determines the amount of money each network pays per viewer: |

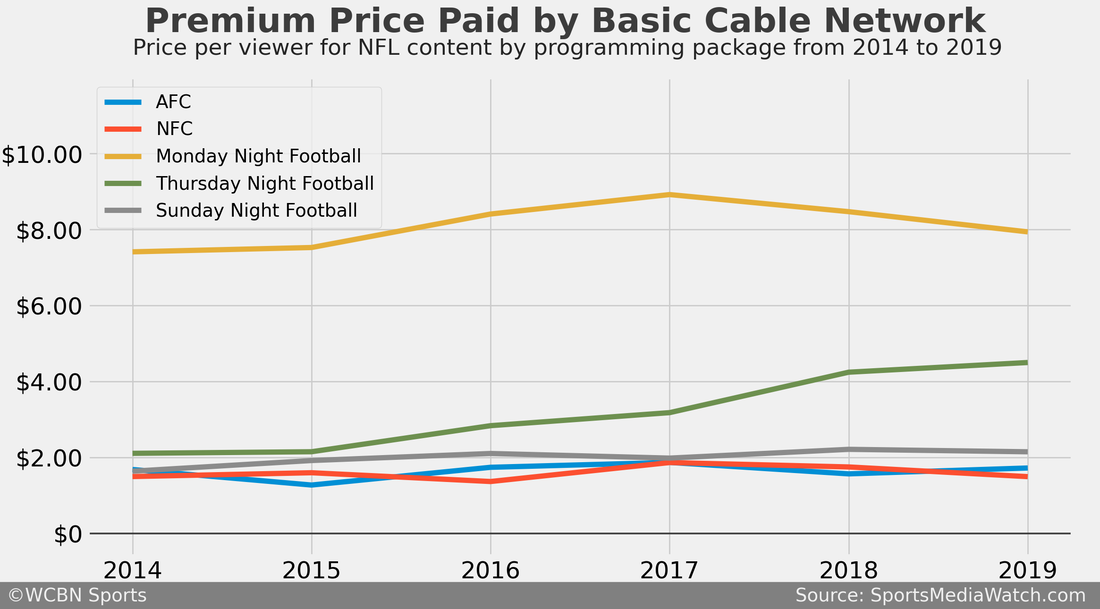

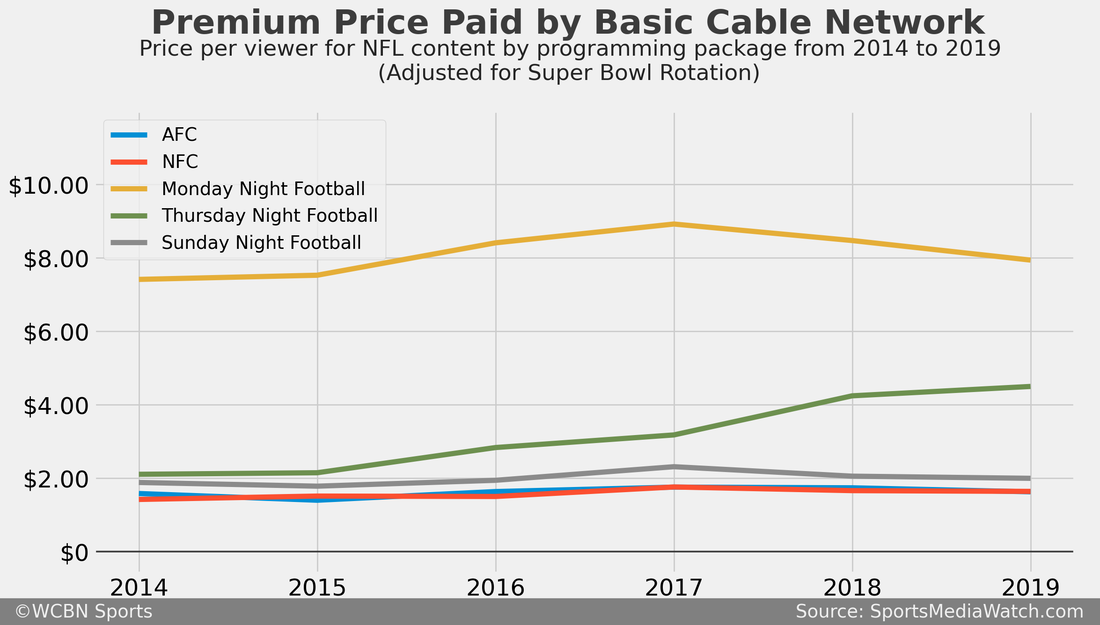

| It is important to note that these calculations only consider the size of the NFL broadcast contracts. Additional production and personnel costs (such as the recent blockbuster contract given to Tony Romo, valued at $17 million per year) are not included in these calculations, but it is likely a drop in the bucket compared to the behemoth NFL contracts. These production and personnel costs likely do not vary much across networks, approximately scaling on a per-game basis. Therefore, networks with primetime packages (ESPN’s Monday Night Football and NBC’s Sunday Night Football) might see a slightly better value than Sunday afternoon packages (CBS’s AFC package and Fox’s NFC Package). The Thursday Night Football package has shifted networks several times since 2014, adding unnecessary complexity to the above graph. Measuring the cost per viewer for each broadcast package, rather than network, removes this complexity: |

| Additionally, each year the Super Bowl rotates between Fox, CBS and NBC. The Super Bowl is the most watched television broadcast each year by a wide margin. Since admittance to this rotation is included in each network’s broadcast package, viewers drawn during each year’s Super Bowl comes at no additional cost to the host network. In a way, seasons when a network broadcasts the Super Bowl effectively subsidize the following two seasons when the championship is broadcast by competitors. Below, this rotation is adjusted for by distributing the Super Bowl viewers equally between the three networks included in the rotation: |

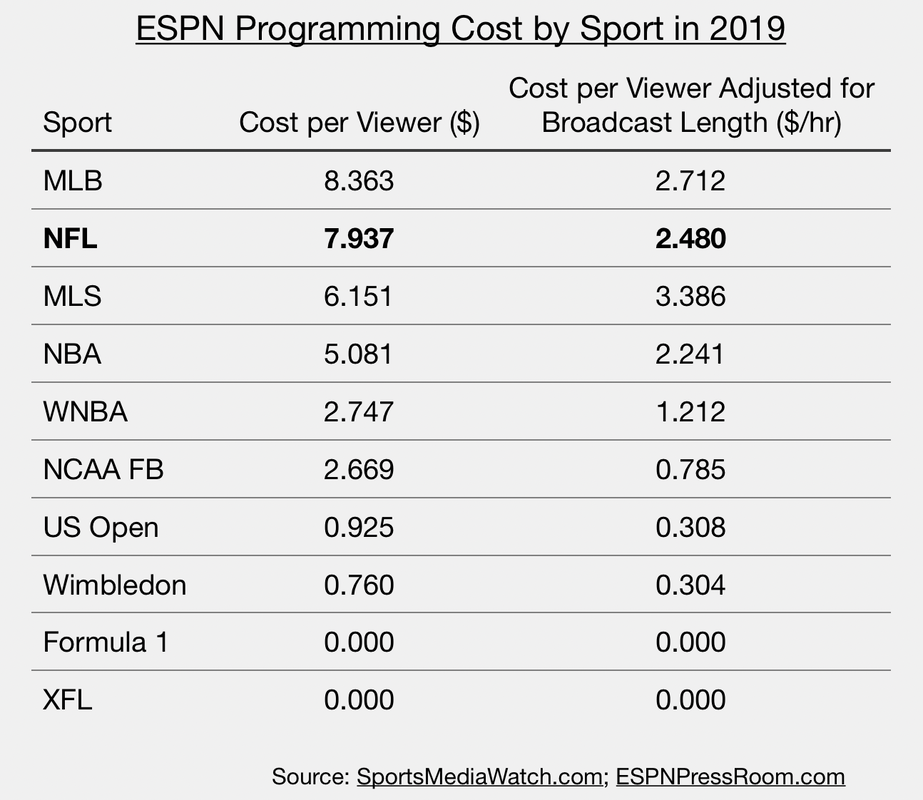

| Accounting for the Super Bowl rotation stabilizes the cost per viewer by network from year to year. The two Sunday afternoon packages are almost overlapping and consistently the best value in terms of cost per viewer. Although Fox pays slightly more for the NFC package than CBS pays for the AFC package, it is almost perfectly negated by Fox’s larger viewership. NBC plays slightly more for Sunday Night Football, however it is generally in the same ballpark as the Sunday afternoon packages. Thursday Night Football has seen a steadily increasing cost, driven mainly by near-annual price renegotiations in 2014, 2015, 2016 and 2018. This allowed the NFL to capitalize on the rising market price of professional sports broadcast rights, without having to wait until the expiration of the other contracts in 2022. However, ESPN pays approximately four times more for its Monday Night Football package than CBS, Fox and NBC pay for their respective packages. Why is this the case? Is ESPN simply bad at negotiating? That might be partially to blame. Steve Bornstein, Executive Vice President of Media for the NFL and President of NFL Network, oversaw the 2005 and 2014 contract negotiations with the league’s television partners. Prior to joining the NFL in 2003, Bornstein was president of ESPN and ABC, leaving after clashing with Disney CEO Michael Eisner. The bad blood between Bornstein and his former employer likely factored in ESPN having the most expensive contract during both negotiations. However, ESPN accepts this higher price tag because it has a fundamentally different business model than the other networks. CBS, Fox and NBC are broadcast networks -- meaning that advertising and content licensing fees are their primary sources of revenue. On the other hand, ESPN is a cable network, which allows nearly two thirds of its revenue to come from subscription fees paid by cable television customers, in addition to traditional advertising revenues. Each cable channel collects “affiliate fees” from cable providers to be carried in their cable packages. Most channels charge less than $0.50 per subscriber, per month in affiliate fees. However, ESPN is notorious for charging an industry-high $9.17 affiliate fee, substantially larger than TNT, the next most expensive cable channel, which charges only $2. The affiliate fees of ESPN and other channels have risen rapidly over the past decade. In 2010, ESPN’s affiliate fee was under $2 per subscriber per month. This 20% annual growth in affiliate fees has allowed ESPN’s revenue to rise, even during a decade of accelerated cord-cutting. And the affiliate fee is paid by all cable subscribers, regardless of whether they watch ESPN. Why do cable providers agree to carry ESPN at this absurdly high price? Or why don’t cable providers at least allow subscribers to opt out of the channel? ESPN, as the second most watched cable channel and the most watched among men, has plenty of bargaining power with providers. Much of this leverage is derived from the network’s catalog of live sports, with Monday Night Football being the crown jewel. ESPN is willing to pay more for NFL broadcast rights because live sports allow the channel to charge exorbitant affiliate fees. Although NFL coverage isn’t the only thing preventing cable providers from dropping ESPN, the league’s unmatched popularity makes Monday Night Football an essential aspect of the station's programming lineup. Since affiliate fees are negotiated collectively by media conglomerates, NFL coverage is arguably more important to Disney than ESPN. The Walt Disney Company owns 19 cable channels in the United States, three of which (ESPN, Disney Channel and ESPN 2) are among the ten cable channels with the highest affiliate fees. ESPN’s strong leverage allows its sister channels to negotiate higher affiliate fees than any could individually. ESPN’s strategy to strong arm cable providers with live sporting events might be most visible with NFL coverage, it is not unique to the league. ESPN holds a vast catalog of live programming broadcast rights. In addition to bringing in advertising revenue in their own right, each contract makes ESPN more essential in the eyes of sports fans and cable providers. In fact, the NFL isn’t even ESPN’s most expensive contract in terms of cost per viewer. MLB coverage is approximately $0.30 more expensive per viewer than Monday Night Football. The NFL’s cost per viewer is in the same ballpark as ESPN’s MLB, MLS and NBA coverage. |

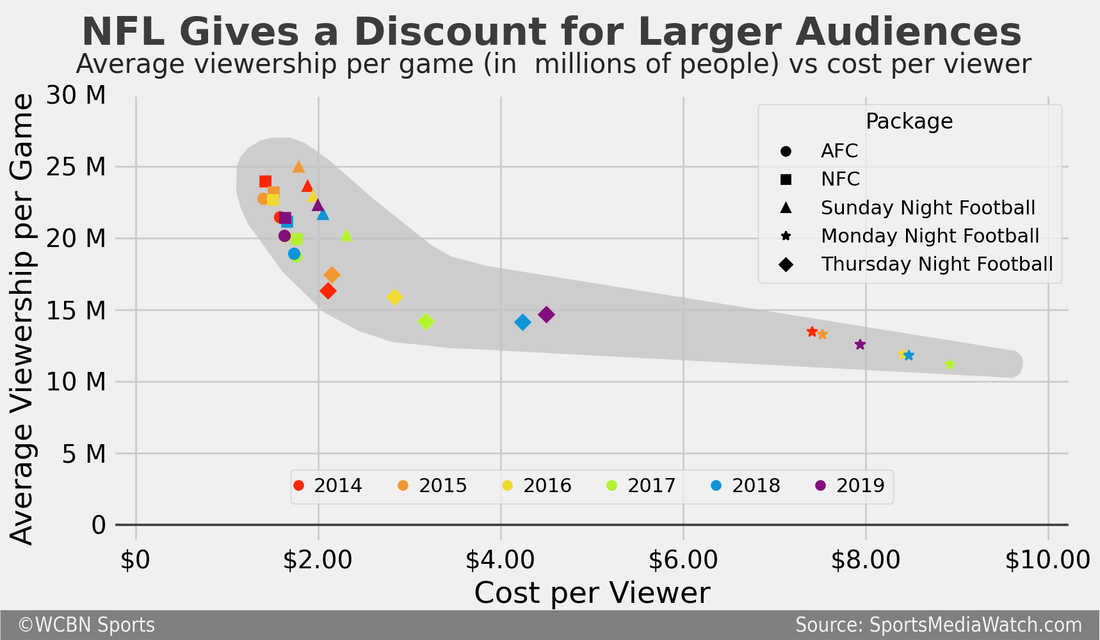

| Interestingly, NCAA Football coverage is relatively a better value than any of the major leagues. Despite the high price tags that ESPN pays for SEC, ACC and College Football Playoffs broadcast rights, the station is able to secure the broadcast rights for minor conferences on the cheap. The network only pays $8 million per year for Mid-American Conference games and $18 million per year for All American Conference games, a drop in the bucket compared to the $300 million ESPN pays the SEC each year. These smaller conferences (along with ESPN’s Football-Industrial Complex) offset the high costs of premier conferences. The best value on a cost per viewer basis are tennis tournaments, along with Formula 1 racing and XFL football. These events are less popular or established than the other leagues and primarily care about public exposure. They are willing to charge less for broadcast rights if it allows their sport to appear on ESPN, the largest and most prestigious sports network in the United States. In fact, the XFL and Formula 1 don’t even charge ESPN for broadcast rights (although the network does cover all production costs). Each assumes that appearing in front of ESPN’s large audience is more valuable than receiving a broadcast contract on a smaller network. Regardless of ESPN’s content strategy, it is worth mentioning that Monday Night Football is successful on its own right, ignoring the leverage that it provides the network. During football season, Monday Night Football is routinely the most viewed cable program each week. Nearly every week, Monday Night Football draws more viewers than broadcast networks during the same time slot. For the past three seasons, Monday Night Football has been the most watched series on cable. Each of these ratings achievements become even more pronounced when accounting only for men in key advertising demographics. If the NFL earns such a large paycheck from ESPN, why doesn’t the league collect similar prices from its other broadcast partners? The answer lies with the size of each network’s audience. Since CBS, Fox and NBC are broadcast networks, rather than a cable channel, their programming reaches more households than ESPN. The broadcast networks are available in 120 million homes in the United States whereas ESPN is only available in 87 million homes. The NFL clearly values the larger reach of broadcast networks, and is willing to give them a discount during contract negotiations. Below is a graph that compares the cost per game with the average viewership of each programming package: |

| As expected, the NFL generally charges less for broadcast rights that will appear in front of a larger audience. Besides direct increases in revenue, a large audience provides more exposure to the league, increasing secondary revenue streams such as ticket sales and merchandise. The NFL counts on its massive audience to remain a staple of American culture and society. There aren’t any broadcasters with a larger reach than CBS, Fox and NBC, especially platforms that don’t require a subscription. But if a network with a smaller audience than ESPN decides to bid for broadcast rights during future negotiations, the NFL will probably charge it even more on a per viewer basis than ESPN’s $8.00. In addition to substantial sums collected annually from television contracts, the NFL also sells the digital distribution rights to its games. DirecTV pays $1.5 billion per year to be the exclusive provider of NFL Sunday Ticket, the only legal way to watch live out-of-market games. Verizon pays $500 million per year for the streaming rights for all in-market games, while Amazon pays $65 million per year for the streaming rights for 11 Thursday Night Football games. Each of these streaming packages provides an additional incentive to subscribe to the respective host platform. Amazon hopes that Thursday Night Football coverage will convince more people to sign up for Prime, Verizon hopes its streaming service will entice customers to choose their phone plan over competitors and AT&T, parent company of DirecTV, hopes the exclusive Sunday Ticket encourages people to subscribe to DirecTV over cheaper cable alternatives. None of the digital rights holders receive advertising revenue and only Sunday Ticket charges an additional fee to watch the package. All of these streaming packages are examples of the “loss leader” pricing strategy. Oftentimes, firms will decide to price certain products below market cost in order to increase sales of other products. A famous example is Costco’s $1.50 hot dog and soda combo, which hasn’t seen a price increase since its introduction in 1985. Costco management hopes that the low price draws customers into their superstores, where they might decide to purchase other items. Also, it helps some customers justify the high annual Costco membership. AT&T, Verizon and Amazon take the same approach with their NFL streaming streaming packages. The platforms offer NFL coverage to their subscribers for free, or at a price well below the market cost, in order to increase demand for their respective subscription service. A final stream of media revenue comes from the NFL’s wholly owned subsidiary, the NFL Network. As a cable channel, NFL Network has a similar business model to ESPN: The channel collects monthly affiliate fees from cable providers, regardless if cable customers watch the channel. NFL Network produces original content, simulcasts Thursday Night Football, and is the exclusive broadcaster of all London NFL games. For similar reasons as ESPN, NFL Network commands massive leverage when negotiating affiliate fees. In 2017, the network charged $1.40 per subscriber per month, the fourth highest of all cable channels, behind only Disney Channel, TNT and, of course, ESPN. Multiplying this by NFL Network’s 71 million subscribers and 12 months in a year estimates that NFL Network draws $1.2 billion annually in affiliate fees alone. Between television contracts, streaming contracts and the fully owned NFL Network, the NFL earns a total of $8.25 billion in media revenue each year. Media revenue accounts for over half of the NFL’s total income, making media contracts incredibly important to the financial stability of the league. Other sources of revenue include licensing and merchandise (approximately 10% of the league’s income), corporate sponsorships (also approximately 10% of the league’s income) and gameday revenue, such as ticket sales, concessions and parking (approximately 15% of the league’s income). Without an end in sight to the coronavirus pandemic, the NFL’s media revenue is more important than ever since gameday revenue streams are nonexistent. Now that we know the fundamentals of the economics behind NFL televisions rights, we can speculate what might happen during the upcoming renegotiations. |

The Players:

| The NFL’s four current broadcast partners are all interested in retaining their packages. Despite the high price tag, NFL coverage is nothing short of a jackpot for rights holders. Obviously, NFL games draw huge audiences each week, which can be sold to advertisers for top dollar. Additionally, NFL coverage comes with secondary benefits, such as boosting viewership for pre- and post-game shows and providing prestige for the network. It is unlikely any current broadcaster would decide to give up its slice of the pie unless the price increases dramatically. When Fox outbid CBS for the NFC package in 1993, several CBS affiliates in NFC-hosting media markets decided to switch affiliation to Fox. Later, when CBS outbid NBC in 1998 for the AFC package, NBC’s rating fell to last place among the “big four” broadcasting networks for the first time since Fox was founded in 1986 (Although, it wasn’t all bad because it directly led to the first incarnation of the XFL). It would likely be catastrophic financially for any current broadcaster to lose its NFL rights during the upcoming negotiations. During the 2019 Michigan Sport Business Conference, Sean McManus, the Chairman of CBS Sports, stressed how important it is for his network to retain NFL rights, saying, “Strategically, it is my number one priority to maintain the events that we have.” A similar mindset is likely held by executives at Fox, NBC and ESPN. Besides the four current broadcast partners, few other organizations have both the funding and desire to carry NFL games. An obvious contender might be ABC, the only “big four” over-the-air network that does not currently broadcast the NFL. ABC previously carried Monday Night Football from 1970 until 2005. However, the primary hurdle is that both ABC and ESPN are owned by the Walt Disney Company. Making a move for NFL rights might displace sister network ESPN from its package, while definitely raising the asking price for all packages, as the NFL adjusts to multiple bidders. Even if ABC and ESPN both secure broadcast packages, it is unknown whether Disney would be willing to pay for two hefty contracts. All things considered, ABC is not a favorite to secure an NFL package, but it would not be surprising if it ends up happening. It is also possible that other sports cable channels make an offer for an NFL package. As discussed above, broadcasting live NFL games provides significant leverage during negotiations with cable providers. If NBCSN, FS1, TNT or another sports channel secures NFL rights, they will be able to charge significantly higher affiliate fees, possibly in the same ballpark as ESPN. One concern for this approach is that many cable sports channels already have a hand inside the NFL’s wallet, indirectly. Both NBCSN and NBC are owned by Comcast, which already has the rights to Sunday Night Football; Both FS1 and Fox are owned by News Corp, which already has the rights to the NFC package; Both TNT and DirecTV are owned by AT&T, which already has exclusive access to NFL Sunday Ticket. Among all these options, TNT would be the most likely. The channel already has NBA, MLB and March Madness coverage, so the NFL would fit right into their programming lineup. Additionally, it is possible DirecTV is outbid for Sunday Ticket, so AT&T could attempt to maintain ties with the NFL through TNT. Also, AT&T owns plenty of other cable channels, including TBS, CNN, Adult Swim, HBO and Cartoon Network. If TNT secures an NFL package, AT&T would be able to negotiate higher affiliate fees for all of its sister channels. Since it is 2020, I feel obligated to mention digital companies possibly making a bid. Just as Fox’s 1993 takeover of the NFC package cemented the upstart network as a major media player, any streaming platform to secure a package will instantly become an undisputed media institution, along with the “big four” broadcasters. Companies that might be interested include Google (through its subsidiary YouTube), Apple (through AppleTV+), Amazon (through Amazon Prime Video), and Netflix. These companies have more freedom to define what NFL coverage would look like on their platform, compared to the established broadcast format of the television networks. Even some of the existing broadcast partners might stipulate that a new package include access for their respective streaming services. Disney, CBS and NBC could simulcast games on ESPN+, CBS All Access and Peacock, respectively. AT&T might try to get HBOMax into the action as well. In a similar manner to the NFL’s current streaming platforms, a possible deal with any of these services would provide another incentive for viewers to subscribe, an increasingly difficult task as the streaming market becomes more saturated. Some wild card companies worth mentioning include DAZN, the subscription sports streaming service run by former ESPN president John Skipper, or a non-sports cable channel such as Nickelodeon, USA, BET, FX or others. For the upcoming playoffs, CBS will be simulcasting games on Nickelodeon (both owned by Shari Redstone) in an effort for the NFL to reach younger audiences. If successful, it is possible that other media conglomerates with ties to the NFL might simulcast some games on sister networks with niche audiences. |

The Packages:

| As discussed, the NFL currently has five television packages (AFC, NFC, Sunday Night Football, Thursday Night Football and Monday Night Football), in addition to three streaming packages (Sunday Ticket, in-market and Thursday Night Football). It is very likely that all of these packages continue into the future. In fact, the best way for the NFL to increase its media revenue is by creating new packages. Unfortunately, that is easier said than done. Barring any league expansion (which the NFL is certainly considering, but unlikely to implement in time for the upcoming negotiations), there will be, at most, 16 games every week. It is possible to spread these games out over more packages or remove the exclusive rights to some games. Either of these options will provide more packages to sell to media partners. However, the NFL is still pretty confined in what it can do in practice. Under the Sports Broadcasting Act of 1961, the NFL is granted an antitrust exemption in exchange for certain concessions. These include the league’s inability to broadcast games on Fridays and Saturdays to protect high school and college football, respectively. Therefore, the only days that the NFL is usually able to play are Sundays through Thursdays. Sunday, Monday and Thursday already have games scheduled, and it is unlikely that any large-scale Tuesday or Wednesday night packages occur (outside of freak weather or pandemic situations) due to the limited amount of rest players would receive. However, the Sports Broadcasting Act only prevents the NFL from playing on Fridays and Saturdays until mid-December, which covered the entire NFL regular season when it was enacted. However, today the league plays three regular season weeks after the regulations are lifted, leading to some late-season Saturday Night Football. Maybe the NFL decides to spin the late-season games (often lucrative with playoff implications on the line) off into their own package. This concept would become more viable if the NFL expands its regular season to 17 games, as allowed under the new CBA. The other possibility for a new package is London games. Although it is despised by many players, London games are generally favored by fans because it allows gamedays to begin at 9:30am (a consequence of London’s time-zone). On weeks when London games take place, fans are able to watch non-stop, live football from 9:30 am until 11:30 pm. Currently these games are broadcast exclusively by the NFL Network. It is possible that the NFL decided to sell these games to the highest bidder, similar to what was done with Thursday Night Football in 2014. The consequence of terminating the only games exclusively broadcast on NFL Network is that the channel loses some leverage when negotiating affiliate fees with cable providers. The NFL Network would still command high affiliate fees, but providers might decide to move the channel out of its standard package, decreasing the amount of subscribers. However, the NFL might decide that these losses are less than the gains from selling a “London Morning Football” broadcast package to the highest bidder. In terms of streaming, the NFL has more flexibility. With only three current streaming packages, the NFL might decide to break these down further so more platforms can have a slice of the pie. However, each time the NFL does this, it devalues its existing streaming packages, especially Sunday Ticket. It is also possible that the NFL decides to remove the exclusivity behind Sunday Ticket, allowing multiple platforms to offer the service. ESPN+, AppleTV+, YouTube and DirecTV have all been rumored to be interested in hosting Sunday Ticket. Obviously, this devalues Sunday Ticket in the eyes of platforms, but the move is extremely pro-consumer, allowing more people to watch out-of-market games. Maybe the NFL’s accountants decide that the combined contracts from several platforms plus the goodwill of fans having more (legal) options to watch out-of-market games is greater than the revenue it could receive from an exclusive provider. |

The Cost:

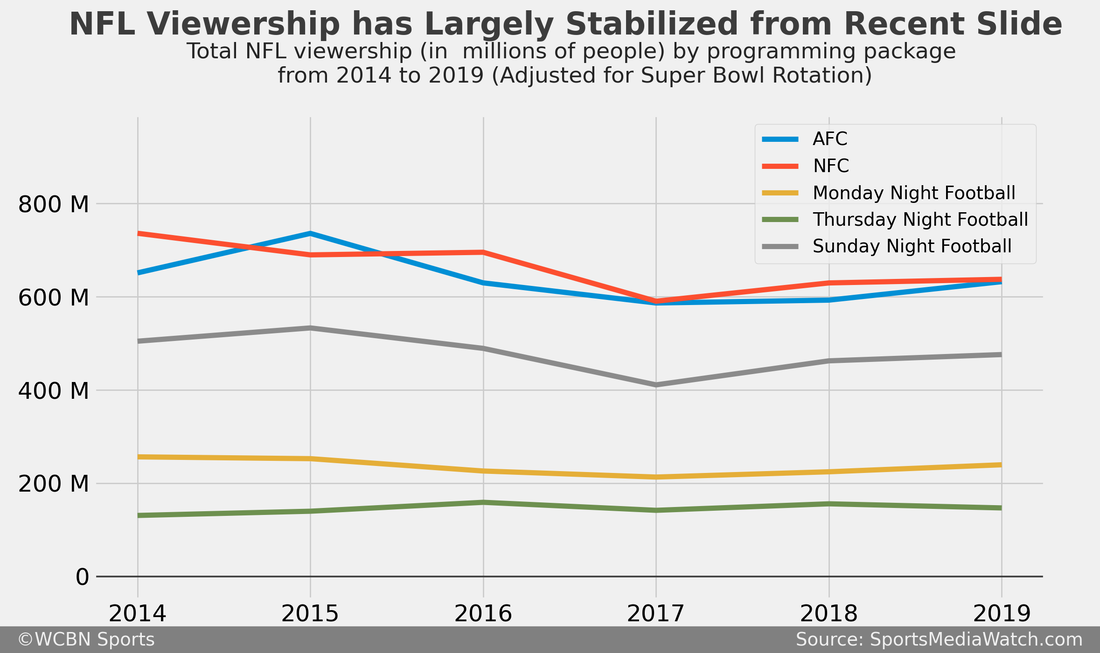

| The billion dollar question (literally) is how much will these packages cost. Despite what some headlines, and the President, declared in 2017, the NFL’s ratings are not in a tailspin. Below is a graph of the total viewership over the entire season of each NFL package: |

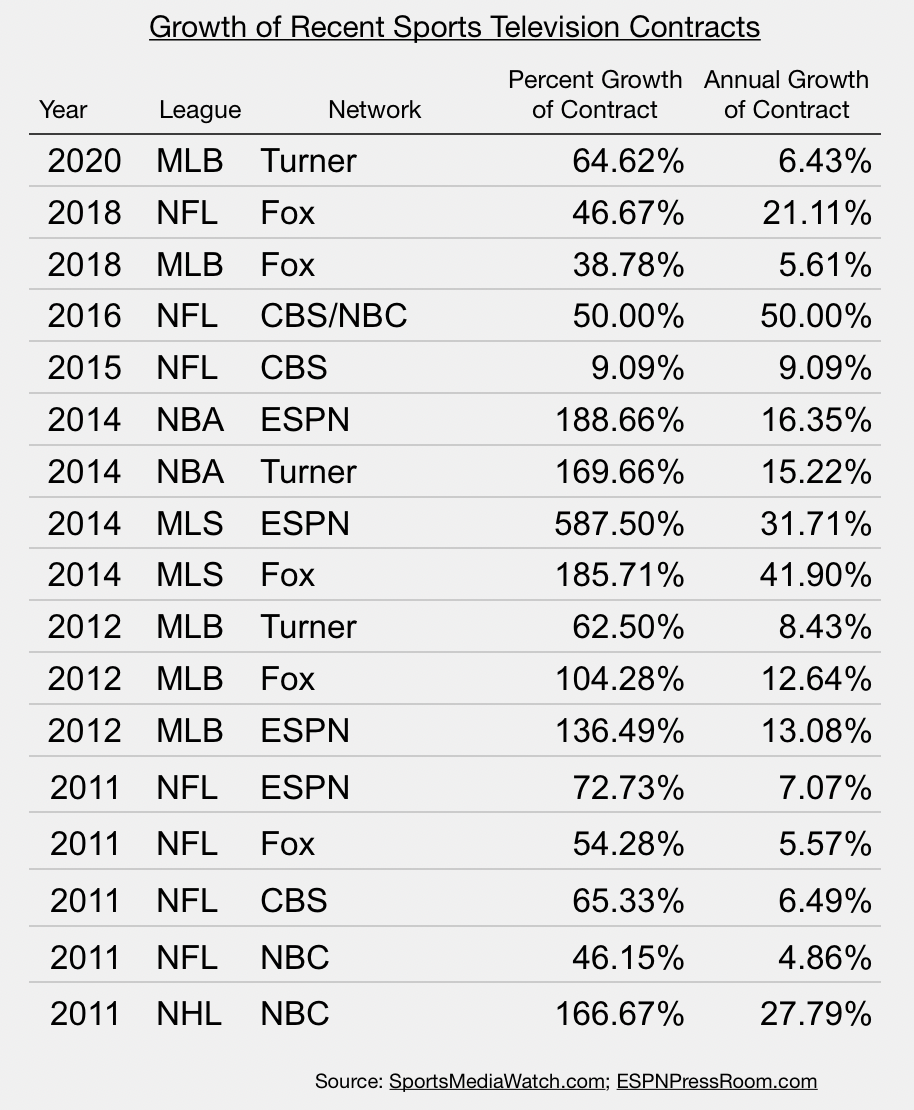

| Yes, the NFL did experience a slight decline in viewership from 2014 to 2017. However, the league has stabilized and even partially bounced back since then. Despite what pundits might claim, the recent viewership slide will be a small consideration during the negotiations. The NFL contract negotiations are perfect examples of the economic model of supply and demand. Supply is limited and unlikely to expand much. There are only five broadcast packages and a handful of streaming packages. In terms of a per-game outlook, there are only 252 regular season games each year, which is fixed (baring a season extension or league expansion). The demand, on the other hand, is enormous. Dozens of organizations would jump at the opportunity to broadcast the NFL, even at expensive rates. As a result of the disparity between supply and demand, a shortage appears, causing organizations to bid up the price of each package until an equilibrium is reached between supply and demand. Therefore, the cost of NFL broadcast contracts will likely rise into perpetuity or until demand for NFL dries up. This economic framework is well understood by the NFL’s Media Committee. The Media Committee is one of the league’s 30 executive committees and oversees the NFL’s relationship with its media partners. The most important task of this committee is to negotiate favorable terms with broadcasters when television contracts are renewed. Among those serving on the committee are some of the most influential NFL owners, including Robert Kraft, Jerry Jones, Jeffrey Lurie and Stan Kroenke. Former NFL Commissioner Paul Tagliabue understood the importance of having a beneficial balance between the number of bidders and the number of packages. Reflecting on the 1993 negotiations that resulted in Fox outbidding CBS, Tagliabue said, “If you have three packages and three bidders, you’re not going to do very well. It’s like musical chairs. You always have to have one more person looking for seats than you have seats. … When you brought new players to the table, it was a different set of negotiations.” It is impossible to know how much the cost of each package will rise during these upcoming negotiations, but you can make an educated guess based on other recent television contract extensions in other professional leagues. Below is a table listing all of the broadcast contracts in the five major professional sports that were signed over the past decade: |

| Additionally, the table lists the percent growth of each contract over its predecessor. This can sometimes be deceiving, especially since contracts across sports and within the same sport, can have massively varying length. Therefore, the table also calculates the annual growth of each contract, so the figures are more comparable. Over the past decade, the annual growth in television contracts has varied from 4% to 50%. The upcoming NFL contracts are likely to have similar annual growth rates to the most recent widespread negotiations that occurred in 2011. Those contracts, which are still in effect today, had an annual growth between 4.8% and 7.1% over their respective predecessors. I would expect that the next round of NFL contracts will likely experience an annual growth of 5% to 8% above the current contracts. On the low end, this means that annually the AFC package will likely cost $1.6 billion, the NFC package will cost $1.7 billion, Monday Night Football will cost $2.9 billion and Sunday Night Football will cost $1.5 billion. On the high end, the AFC package could cost $2.05 billion, the NFC package $2.2 billion, Sunday Night Football $3.6 billion and Sunday Night Football $1.9 billion. These figures are in line with analysts estimates: a source at CNBC expects the Sunday afternoon packages to go for around $2 billion annually and Monday Night Football to go for around $3 billion annually. All of these estimates presume each network retains their current package. As discussed earlier, the NFL has shown willingness to offer a discount on broadcast deals if the package will expose the sport to a wider audience. Therefore, if a cable channel or a streaming platform (all with a smaller reach than any current media partner) makes a move for one of the broadcast packages, expect the price to increase even more. The NFL also takes other factors into consideration when negotiating media packages. As mentioned, the NFL values broad distribution. Other factors include the ratings stature of the network, the broadcast and production talent of the network and possible cross promotion that the network can enact. These considerations explain why CBS decided to give Tony Romo a massive payday and why you see frequent references to upcoming NFL games on unrelated shows. All four of these factors favor traditional broadcast networks, but as Fox proved in 1993, can be overcome by an offer well above market. |

The Length:

| The final question mark of the upcoming negotiations is how long will the new contract be. The NFL likes to keep all of its contracts about the same length, leaving the option for packages to be scrambled between broadcasters, which ultimately works to raise the price. Additionally, both broadcasters and league executives prefer a longer contract. For broadcasters, this provides some cost savings when it is presumed that the price will continue to rise every year. For the league, this provides stability, a necessity when rating slides or a global pandemic are possible. It is likely that all contracts will be a similar length as the previous contract, which lasted eight seasons. Sources with CNBC estimate that the new contracts will likely be seven or eight-year deals. |

Conclusion:

| The upcoming NFL contract negotiations are an opportunity for broadcasters and the league to lock in profits. I would expect that the league will sign extensions with all of its current media partners, with each package costing roughly $1 billion more annually than the current contract. Additionally, the contracts will be eight year deals, lasting through Super Bowl LXVIII in 2030. The most likely contract to change hands is the Sunday Ticket, which has the opportunity to find a new owner or potentially be split among several platforms. But, in a year that has been anything but predictable, don’t be surprised if Roger Goodell pulls off something completely unexpected. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed